Although Acanthostega had legs, they were probably not used for walking because its feet could not support it.

When scientists first discovered Acanthostega, they only found parts of a skull. Very recently, they found a more complete skeleton.

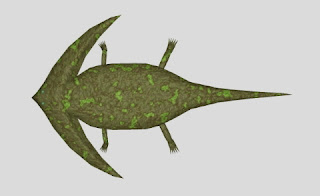

Acanthostega had a leaf-shaped tail, which could have helped it swim. It was about 2 feet long and was probably a descendant of the Sarcopterygii (lobe-finned) fishes Tiktaalik and Panderichthys, and an ancestor of the land-dwelling tetrapod Ichthyostega.

Acanthostega probably lived in swamps full of plants and debris. It was one of the first animals to catch prey by actually biting it, unlike fish, which simply had to suck food in. Acanthostega probably fed by swimming close to shore and grabbing prey with its mouth, or catching things with its head above the water. It had eight digits on the front feet, and maybe even on the hind feet.