Phlegethontia is a snake-like amphibian that lived from the Carboniferous to the Permian period. It lived in swamps and probably, unlike most snakes today, spent most of its time swimming in water, like a frog or a newt. Phlegethontia was about one meter long and it ate small animals and insects.

Phlegethontia was found in the Mazon Creek, in Illinois, among other places. The skull had holes in it, and this made it light. My hypothesis is that Phlegethontia evolved this way because a lighter skull would be easier to lift, and therefore it would be easier for Phlegethontia to snatch a flying insect from the air, much like this adaptation makes it easy for a snake to strike quickly. The skull of Phlegethontia is similar to that of a snake.

Phlegethontia looked very much like a snake, suggesting a similar lifestyle, except more in the water than on land. Amphibians like Phlegethontia cannot permanently live on land without getting wet because they would dry out and die.

At one time there was something called Dolichosoma longissima. But this was an incorrect description and paleontologists realized that it was actually a member of the genus Phlegethontia. Now it is called Phlegethontia longissima.

References:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phlegethontia

http://dinosaurs.about.com/od/tetrapodsandamphibians/p/phlegethontia.htm

Showing posts with label Permian. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Permian. Show all posts

Friday, January 27, 2012

Saturday, January 14, 2012

Helicoprion (Part 2).

I've already posted Helicoprion before on my blog, as my very first post. But I have learned so much since then that I would like to write about some new information.

Helicoprion had a buzzsaw-shaped tooth whorl on its lower jaw, which is what it's famous for. The most up-to-date reconstruction suggests it being a shark-like fish with a long upper jaw and a long lower jaw. At the end of the lower jaw was where the tooth whorl was.

Although most specimens of Helicoprion's tooth whorl are about 10 inches in diameter, one specimen has a diameter of about 2 feet, suggesting that this odd shark-like cartilaginous fish might have grown more than 32 feet long, which makes Helicoprion one of the largest cartilaginous fish of all time. Only Megaladon, which didn't appear until the Tertiary period, was larger.

Fossils of Helicoprion have been found all over the world, as far apart as Australia and North America. The first remains were found in Russia and were named Helicoprion bessonovi. Other fossils of Helicoprion bessonovi have been found in China, which is not surprising to me because they were nearby. At the time that Helicoprion lived, all the continents were together, which probably explains why it has been found in so many places. In the United States, fossils of Helicoprion are found mostly in the western states, near where fossils of the related Edestus have been found.

Helicoprion lived from the Carboniferous to the Triassic, which is quite a long time for a single genus to be around.

References:

http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2011/03/unraveling-the-nature-of-the-whorl-toothed-shark/

http://www.paleospot.com/galerie_rubrique.php?rub=2 (lots of amazing illustrations of prehistoric sharks)

http://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2011RM/finalprogram/abstract_187593.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helicoprion

Helicoprion had a buzzsaw-shaped tooth whorl on its lower jaw, which is what it's famous for. The most up-to-date reconstruction suggests it being a shark-like fish with a long upper jaw and a long lower jaw. At the end of the lower jaw was where the tooth whorl was.

|

| © Life Before the Dinosaurs 2012 |

Although it is sometimes reconstructed eating ammonites, the absence of broken teeth on most specimens of its tooth whorl suggests that instead of eating ammonites, it fed on animals such as squid, fish, and other animals without shells.

Although most specimens of Helicoprion's tooth whorl are about 10 inches in diameter, one specimen has a diameter of about 2 feet, suggesting that this odd shark-like cartilaginous fish might have grown more than 32 feet long, which makes Helicoprion one of the largest cartilaginous fish of all time. Only Megaladon, which didn't appear until the Tertiary period, was larger.

|

| © Shark Trust |

Helicoprion lived from the Carboniferous to the Triassic, which is quite a long time for a single genus to be around.

|

© Oleg Lebedev 2009 |

References:

http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2011/03/unraveling-the-nature-of-the-whorl-toothed-shark/

http://www.paleospot.com/galerie_rubrique.php?rub=2 (lots of amazing illustrations of prehistoric sharks)

http://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2011RM/finalprogram/abstract_187593.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helicoprion

Friday, December 23, 2011

Conodonta.

Conodonts were bizarre, fish-like probable chordates that may have resembled modern lampreys. They first evolved in the Cambrian, or possibly even the Precambrian, and died out in the Triassic-Jurassic extinction.

Conodonts were eel-shaped in form and most had large eyes, at least in comparison to the body. They had various toothy blades in the mouth to form what is known as "the conodont apparatus," which vaguely resembles the radula of a snail or slug.

Conodonts were probably capable of maintaining a cruising speed, but could not perform bursts of speed because their eel-like form would probably get them all tangled up. They would then be easy prey for any kind of predator trying to eat them. They probably swam in about the same style as an eel or loach. Although they had sharp teeth, they probably were not predators. Instead, they supposedly used "the conodont apparatus" as a sort of baleen to filter plankton from the water.

The largest conodont that has been found so far is Promissum, which reached lengths of 16 inches. Specimens of Promissum can be found in the Soom Shale of South Africa. Unlike most conodonts, Promissum had smaller eyes relative to body size. Promissum was about as long as an average house cat's body, without the head or tail.

The fist conodont specimens found were its individual toothy bars known as "conodont elements."

References:

http://www.ucl.ac.uk/GeolSci/micropal/conodont.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conodont

http://oceans1.csusb.edu/cdont_art.htm

Conodonts were eel-shaped in form and most had large eyes, at least in comparison to the body. They had various toothy blades in the mouth to form what is known as "the conodont apparatus," which vaguely resembles the radula of a snail or slug.

Conodonts were probably capable of maintaining a cruising speed, but could not perform bursts of speed because their eel-like form would probably get them all tangled up. They would then be easy prey for any kind of predator trying to eat them. They probably swam in about the same style as an eel or loach. Although they had sharp teeth, they probably were not predators. Instead, they supposedly used "the conodont apparatus" as a sort of baleen to filter plankton from the water.

The largest conodont that has been found so far is Promissum, which reached lengths of 16 inches. Specimens of Promissum can be found in the Soom Shale of South Africa. Unlike most conodonts, Promissum had smaller eyes relative to body size. Promissum was about as long as an average house cat's body, without the head or tail.

The fist conodont specimens found were its individual toothy bars known as "conodont elements."

References:

http://www.ucl.ac.uk/GeolSci/micropal/conodont.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conodont

http://oceans1.csusb.edu/cdont_art.htm

Labels:

Cambrian,

Carboniferous,

Devonian,

ordovician,

Permian,

Precambrian,

Silurian,

Triassic

Saturday, September 24, 2011

Edaphosaurus.

Edaphosaurus was a genus of sail-back synapsid, a group of animals that includes mammals and their relatives. It lived from the late Carboniferous to the early Permian. Even though Edaphosaurus resembled a dinosaur, they were not dinosaurs. They are actually ancestors of early mammals.

The image below shows Edaphosaurus (the lizard-like one with the sail on its back), and the sail-back amphibian Platyhystrix. For some reason this interpretation of Platyhystrix does not have the sail on its back.

Edaphosaurus had spines that held up its "sail." These spines also had small knobs sticking out of them. Scientists think that Edaphosaurus's "sail" was either for warming its body, for attracting a mate, or both. It's possible that it was for the same purpose as antlers or horns on modern day mammals like deer or goats. But nobody really knows what the "sail" was for.

Edaphosaurus was similar to Dimetrodon, but was smaller. Edaphosaurus was three to eleven feet long, and may have been prey for Dimetrodon.

Edaphosaurus was an early plant-eating tetrapod, but it may have not eaten plants, but instead hunted small animals such a mollusks. Or it could have eaten both and been an omnivore.

Most fossils of this synapsid only show teeth and bits of its backbone. Edaphosaurus is rare and its habits are poorly known.

References:

http://www.utexas.edu/tmm/sponsored_sites/dino_pit/edaphosaurus.html

http://dinosaurs.about.com/od/predinosaurreptiles/p/edaphosaurus.htm

http://www.dinosaurfacts.org/edaphosaurus

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edaphosaurus

The image below shows Edaphosaurus (the lizard-like one with the sail on its back), and the sail-back amphibian Platyhystrix. For some reason this interpretation of Platyhystrix does not have the sail on its back.

Edaphosaurus had spines that held up its "sail." These spines also had small knobs sticking out of them. Scientists think that Edaphosaurus's "sail" was either for warming its body, for attracting a mate, or both. It's possible that it was for the same purpose as antlers or horns on modern day mammals like deer or goats. But nobody really knows what the "sail" was for.

Edaphosaurus was similar to Dimetrodon, but was smaller. Edaphosaurus was three to eleven feet long, and may have been prey for Dimetrodon.

Edaphosaurus was an early plant-eating tetrapod, but it may have not eaten plants, but instead hunted small animals such a mollusks. Or it could have eaten both and been an omnivore.

Most fossils of this synapsid only show teeth and bits of its backbone. Edaphosaurus is rare and its habits are poorly known.

References:

http://www.utexas.edu/tmm/sponsored_sites/dino_pit/edaphosaurus.html

http://dinosaurs.about.com/od/predinosaurreptiles/p/edaphosaurus.htm

http://www.dinosaurfacts.org/edaphosaurus

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edaphosaurus

Thursday, August 25, 2011

Fusulinida.

Fusulinids are extinct single-celled organisms called protists that lived from the Silurian to the Permian. Most fusulinids were about the size of a grain of rice, but some were up to two inches long. They had a hard wall that protected the cell inside.

Some fusulinids are so similar in shape that scientists have to use a cross section of the fossil to identify them.

Fusulinids probably lived in clear water and may have lived on reefs.

Fusulinids are very large and complex for single-celled life, which is usually microscopic. Fusulinids are marker fossils, which means by looking at the fusulinids in a rock formation, scientists can tell how old the rock is.

Note: Edited 8/31/11 to remove the word "animal" and replace it with "organism." Fusulinida was a protist, not an animal.

Some fusulinids are so similar in shape that scientists have to use a cross section of the fossil to identify them.

Fusulinids probably lived in clear water and may have lived on reefs.

Fusulinids are very large and complex for single-celled life, which is usually microscopic. Fusulinids are marker fossils, which means by looking at the fusulinids in a rock formation, scientists can tell how old the rock is.

Note: Edited 8/31/11 to remove the word "animal" and replace it with "organism." Fusulinida was a protist, not an animal.

Wednesday, August 24, 2011

Archimedes.

Archimedes (bryozoan) is an extinct animal that lived from the Carboniferous to the Permian Period. Archimedes had a spiral wall that wrapped around a corkscrew stalk that was anchored to the sea floor. The wall was covered in zooids, like all bryozoans.

Archimedes is named after the Archimedes Screw, because of the corkscrew stalk. Most fossils of Archimedes do not preserve the spiral wall. Instead they only preserve the unusual stalk.

Archimedes is unique because of its spiral shape. It is a kind of animal called a bryozoan, which means "moss animal." They are also commonly called "moss animals," and they are still alive today. But Archimedes has been extinct since the Permian.

These fossils of Archimedes only preserves the corkscrew stalk. The rest of it is usually not preserved because it is very brittle, like all bryozoans.

Monday, July 25, 2011

Sigillaria.

Sigillaria (sidge-ill-AIR-ee-uh) is a genus of lycopod that lived from the Carboniferous to early Permian Period. It had a forked top with a club of pine needle-like leaves on both branches. Although Sigillaria and other lycopods resembled trees, they are their own group. They are actually very different from true trees. Sigillaria was not made of wood and its trunk was covered in photosynthetic tissue, so its trunk may have been green.

Sigillaria was very similar to Lepidosigillaria, which didn't have a forked top. Instead, it only had one club of leaves.

Sigillaria had a short life cycle and only lived for a few years. Some people believe that Sigillaria may have died after reproduction, but no one has found any proof of this.

Sigillaria reproduced with spores like other lycopods. It probably lived alongside other lycopods, such as Lepidodendron, and may have grown to 130 feet.

Sigillaria was very similar to Lepidosigillaria, which didn't have a forked top. Instead, it only had one club of leaves.

Sigillaria had a short life cycle and only lived for a few years. Some people believe that Sigillaria may have died after reproduction, but no one has found any proof of this.

Sigillaria reproduced with spores like other lycopods. It probably lived alongside other lycopods, such as Lepidodendron, and may have grown to 130 feet.

Thursday, July 21, 2011

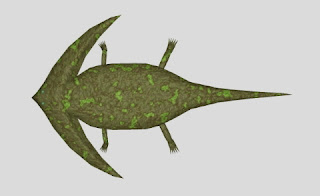

Diplocaulus.

Diplocaulus was an usual genus of boomerang-headed amphibian from the Permian Period. The use for its boomerang-shaped head is a mystery. Maybe it used it to glide through the water like a hydrofoil, or maybe it used it to dig up food, maybe for fighting for a mate, or maybe something else. Very young Diplocaulus did not have the boomerang-shaped head, but older Diplocaulus eventually grew it.

Many fossils of Diplocaulus show that a predator must have been eating it, because they were torn apart and have fossilized teeth in them. The teeth belonged to Dimetrodon. It's not obvious how any predator would have been able to eat Diplocaulus without being choked by swallowing its head. But if something could eat it piece by piece, it would be able to avoid swallowing the head. So synapsids like Dimetrodon would not have trouble eating it.

Diplocaulus was about three feet long. Its closest relative was Diploceraspis, which also had a boomerang-shaped head and resembled Diplocaulus in many ways.

Many fossils of Diplocaulus show that a predator must have been eating it, because they were torn apart and have fossilized teeth in them. The teeth belonged to Dimetrodon. It's not obvious how any predator would have been able to eat Diplocaulus without being choked by swallowing its head. But if something could eat it piece by piece, it would be able to avoid swallowing the head. So synapsids like Dimetrodon would not have trouble eating it.

Diplocaulus was about three feet long. Its closest relative was Diploceraspis, which also had a boomerang-shaped head and resembled Diplocaulus in many ways.

Sunday, July 17, 2011

Cooperoceras.

Cooperoceras was an odd genus of nautiloid cephalopod from the Permian Period. It looked like a spiny ammonite. Cooperoceras was about 4 inches long and 3 inches high. It probably had to avoid edestids, like Helicoprion, Parahelicoprion, and Sarcoprion, because their saw-like jaws could easily smash any kind of shell.

Since all Cooperoceras's living relatives, like squid, cuttlefish, octopus, and nautilus, are carnivores, scientists believe that Cooperoceras was also a carnivore which ate small animals such as echinoderms, bivalves, gastropods, and trilobites. Its spines were probably either for defense, telling each other apart, or attracting a mate.

Cooperoceras had a siphuncle and septa like Orthoceras. But unlike Orthoceras, it had a coiled shell which would have allowed it to live deeper in the ocean than an orthocone's shell would. Even though Cooperoceras had a coiled shell, it was not an ammonoid, because ammonoids do not have the operculum and Cooperoceras did. An operculum is part of the shell that can open and close to give the animal better protection from predators.

Don't forget to enter for a chance to win a Life Before the Dinosaurs t-shirt!

Since all Cooperoceras's living relatives, like squid, cuttlefish, octopus, and nautilus, are carnivores, scientists believe that Cooperoceras was also a carnivore which ate small animals such as echinoderms, bivalves, gastropods, and trilobites. Its spines were probably either for defense, telling each other apart, or attracting a mate.

Cooperoceras had a siphuncle and septa like Orthoceras. But unlike Orthoceras, it had a coiled shell which would have allowed it to live deeper in the ocean than an orthocone's shell would. Even though Cooperoceras had a coiled shell, it was not an ammonoid, because ammonoids do not have the operculum and Cooperoceras did. An operculum is part of the shell that can open and close to give the animal better protection from predators.

Don't forget to enter for a chance to win a Life Before the Dinosaurs t-shirt!

Friday, July 8, 2011

Dimetrodon.

Dimetrodon was an apex predator that lived in the Permian period. There are fifteen species of Dimetrodon. It had a huge sail on its back, which was probably used to warm Dimetrodon up faster than its prey could, so its prey would not be fast enough to escape. Dimetrodon's sail could also have been for attracting a mate. The sail was made up of spines covered in flesh, and each spine was sticking out of a single vertabra.

Dimetrodon probably ate animals such as Edaphosaurus. It had two kinds of teeth, canine teeth and teeth for shearing. Dimetrodon and other synapsids were the first tetrapods to have more than one kind of teeth, like modern mammals do.

Dimetrodon was one of the top predators of its time. It probably ate whatever it could get, including other Dimetrodon. If it couldn't find enough food, it may have eaten other Dimetrodon.

Dimetrodon probably ate animals such as Edaphosaurus. It had two kinds of teeth, canine teeth and teeth for shearing. Dimetrodon and other synapsids were the first tetrapods to have more than one kind of teeth, like modern mammals do.

Dimetrodon was one of the top predators of its time. It probably ate whatever it could get, including other Dimetrodon. If it couldn't find enough food, it may have eaten other Dimetrodon.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)